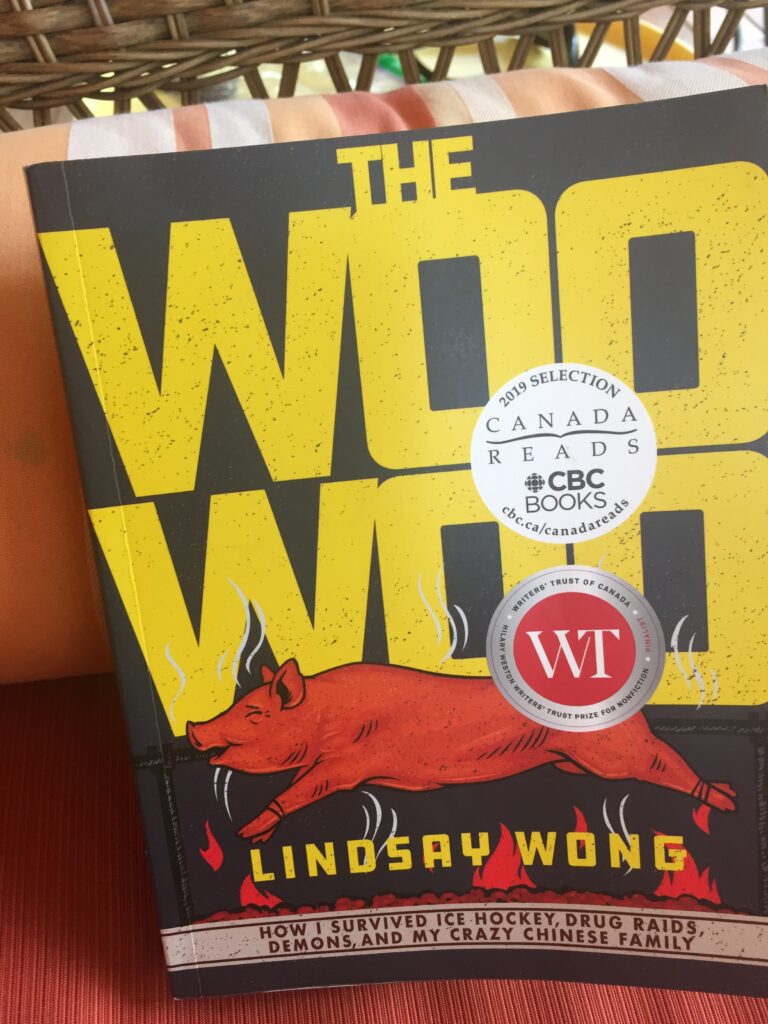

Title: The Woo Woo: How I Survived Ice Hockey, Drug Raids, Demons and My Crazy Chinese Family

Author: Lindsay Wong

Date Read: July 16, 2019

Two snaps

Almost unbelievable. Like, when Oprah couldn’t seem to wrap her mind around James Frey’s memoir… but here it was, wildly incredible– but just grounded in enough legitimacy that you have to let go and trust Lindsay Wong as she recounts her wildly eccentric life with keen prose that is at once castigating of her parents and her upbringing and also graciously sympathetic to the mental illness that ran unchecked amongst them all.

In the prologue Wong sets us up for the ride. Finding herself in a neurologist’s office in Manhattan, she discovers that she has migraine-related vistibulopathy– an intense neurological disorder that plagues her with acute vertigo. This diagnosis is a relief to her, because it is not the Woo-Woo. The Woo-Woo are the ghosts that her Chinese family believed responsible for cancer, viruses, and psychological disturbances– and she and her family actively evade the Woo-Woo as best they can by camping out in Walmart parking lots, not sitting too long on the toilet, or living at the mall eating processed food and endless amounts of candy.

As a parent, my heart ached for Lindsay and her siblings and the disregard for their emotional and physical well-being as centuries-old beliefs kept her grandparents, parents, aunts and uncles from facing and treating the mental illnesses that made them unprepared and unable to cope with the needs of their generations of children. These disorienting relationships left Lindsay feeling crushingly alone, and often pushed her to react and retaliate with physical anger. A lot of her physical aggression was meted out as a goon in the hockey rink– and widely championed by her parents as they collected her medals and encouraged her high-sticking and brutal checking.

Wong offers an unflinching look at mental illness. Hers was a life filled with anxiety and uncertainty, where her needs were often neglected as she competed with the symptoms of her family’s crippling mental illnesses. Wong miraculously succeeds despite it all and shows a personal resiliency and fortitude beyond what could ever be expected.

It is a stunning memoir. Like a car crash in slow motion– you cannot look away. It is heart-breaking, candid, and somehow all at once funny, bitter and melancholy. It is a must-read. Wong’s bravery in telling this story makes her the real poster child for the Let’s Talk About Mental Illness campaign.

A 2019 Canada Reads contender.