Welcome to A Wing East Diaries!

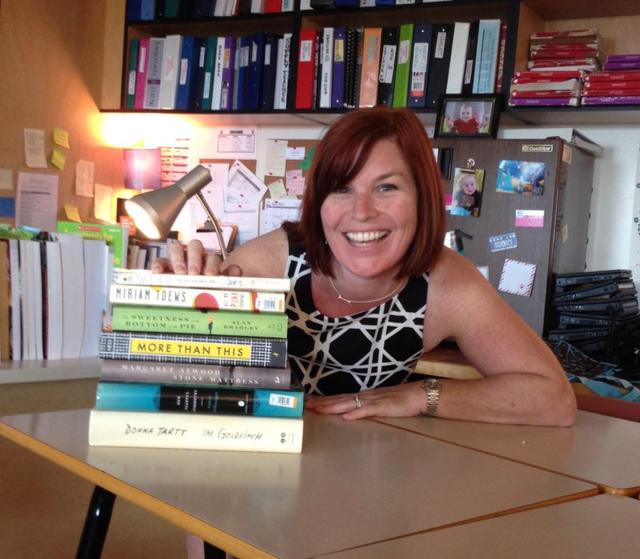

I'm Michelle Wuest, a high school teacher with a deep passion for reading and literature. This blog is my space to share my reading journey, explore the books that move me, and reflect on how literature connects to both my classroom and my life.

As a teacher, I'm always looking for books that will engage my students, but I'm also a reader who simply loves getting lost in a good story. Each book I read becomes a conversation starter, a teaching tool, and a window into different perspectives and experiences.

What are Book Snaps?

My blog posts follow a unique three-part format exploring each book through the lens of reading, teaching, and living.

Learn more about Book Snaps →